Why, Where and How?: Investigating small mammals remains - Part 1

A word of introduction for Part 1

By Andrzej A. Romaniuk (PhD in archaeology, MSc in osteoarchaeology)

Having a chance from the Orkney Museum, I would like to present here a blog entry about my PhD research. While the results have been shown several times during international conferences, I must admit I have not yet properly tried to convey my work significance to a wider audience, especially in a format longer than a couple of paragraphs. As a non-native speaker, it is in part due to my own lack of writing skills. However, a PhD-level work is often a lonely and stressful experience, in a way isolating young researchers from any audience besides the immediate cycle of collaborators, conference attendees and various journal editorial boards. A less formal writing form can be a great way of getting out of this stressful isolation, and perhaps finding further value in one’s work not yet noticed by an aspiring academic.

Research results can be very hard to convey to someone not familiar with the topic. In my case, I think it is more important to showcase how research is being made, from reasons and tools utilized up to issues encountered along the way, with results being briefly mentioned in the very end. In today’s academic reality research does not necessarily follow only one scientific discipline and its methodology, but often branches to others to better study and explain observed phenomena. That is why I will try to first explain “what”, “where”, “why” and “how” (PART 1), with details about my research left for another blog post (PART 2).

I would thank Dr Robin Bendrey (University of Edinburgh) and Dr Jeremy Herman (National Museums Scotland), whose ongoing support was crucial for the completion of this research. I would also like to thank Dr Gail Drinkall (Orkney Museum) for the interest in my work and support in obtaining necessary materials.

What are micromammals?

For well over six years, and through two different degrees, I have been working with the smallest species of mammals encountered on Orkney: common (Orkney) voles, field and house mice, black and brown rats, and pygmy shrews. Terrestrial species like these are sometimes called “micromammals” by professional zoologists and other scientists, as their weight at most is measured in hundreds of grams, with their bodies easily fitting into one’s palm. It may come as a surprise, but well over 50% of all known mammal species can be considered micromammals, making them the biggest, and most diverse, part of the mammalian kingdom.

Why we study them?

However, I do not work with living specimens, but rather their remains, specifically bones and teeth retrieved during archaeological digs (Fig. 1). It may sound odd, given how often such finds can be found in one’s backyard with an hour of shovelling, but they can be a great source of information about the past. Due to a very short lifespan and a high reproduction rate, micromammals can adapt rapidly to any changes in their vicinity, both environmental and man-made. Archaeological finds of specialised micromammals, with their own preferences towards food, weather and the relationship with other animals, can tell us much about how the environment looked and what species may have occupied it in a specific period of time. In turn, remains of species closely related to humans, such as e.g. house mice or guinea pigs, may help in understanding past human behaviour. In the case of house mice, their strong reliance on humans makes them a perfect proxy to reconstruct patterns of human migrations or shifts in subsistence strategies. In turn, guinea pigs show a different spectrum of human behaviour, from being utilized as a food and a status symbol in the pre-Columbian societies of Southern America up to being widely known, lovable pets in modern times.

Why I wanted to study them on Orkney?

But why study small mammals from the Orkney islands, especially given how few species there are in contrast to Mainland Britain or continental Europe? Primarily, because of how intertwined is the history of terrestrial species on Orkney with human migrations and gradual transformation of the isles’ nature to suit farming, herding and fishing. When the glaciation ended, a rapidly rising sea level cut Orkney off from the rest of Britain relatively quickly, resulting in no other way to get there than to swim through Pentland Firth. Therefore all terrestrial mammals currently living on Orkney, including micromammals, were introduced by people, intentionally or not, through the last six thousand years (see Fig. 2). It provides an interesting opportunity to see when and what species were introduced in specific time periods, what was the likely initial reason for introduction, how they adapted to insular life and whether further introductions or changes in human activity have affected their populations. Moreover, a relatively low number of species and a relative ease in connecting changes occurring to external stimuli, renders Orkney really helpful in establishing methods to be later used in more complex cases. In the case of Continental Europe, dozens of micromammal species are often found during archaeological digs, making research on their remains really challenging to provide conclusive results up to a species level.

How we research them?

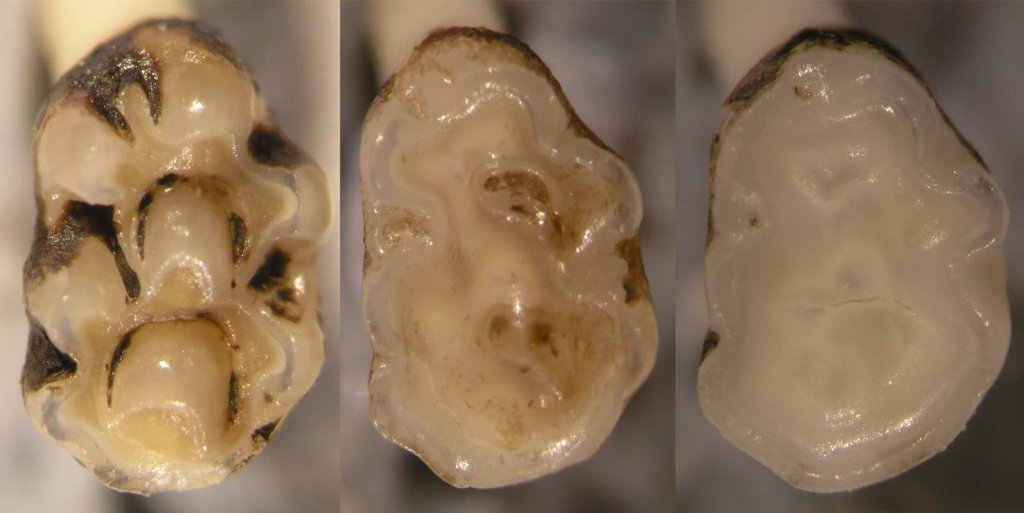

There is a variety of approaches through which micromammal remains can be explored, though many require the use of microscopes or more complex documentation techniques due to how small micromammal bones and teeth often are (see Fig. 3). Starting from basics, the best way of identifying any animal up to specific species, as well as estimating the age or health of an animal, is through checking their teeth. Especially molars are uniquely adapted to a specific diet, resulting in a multitude of different and unique patterns, easily attributable even if worn. Wear itself can be a great indicator of approximate age, especially if there are known modern-day references for the studied species (see Fig. 4). Bones, while harder to discern between specific species, can be nevertheless a never-ending source of data, especially about age (general skeletal development), health (presence of fractures or signs of illness) or specific animal taphonomic history. “Taphonomy” relates to all the processes that happen to the remains from the moment of death until complete destruction or fossilization, including e.g. dismemberment and bone fragmentation, their digestion (Fig. 5), burning or even disappearance from the assemblage. In the case of different predators, one can see a relationship between specific skeletal completeness and other changes, for example owls regurgitating mostly complete skeletons with no, or only mild, digestion marks present, while foxes providing faeces with very few surviving, mostly robust bones. However, micromammals can also die accidentally, e.g. by self-entrapment in man-made features, or due to natural causes. Non-predatory death may denote species nesting nearby, perhaps even within the settlement, with the presence of juvenile specimens pretty much confirming it.

Ending (for now)

I have provided lots and lots of information in this blog post, but what I wish you all to remember from it is that archaeology is a much more complicated subject, going beyond on-field excavations and often blending with other branches of sciences, especially biology. The number of possible factors one has to consider during the research before drawing appropriate conclusions is astonishing, more similar to what we can expect from detective stories with a lab-based work spin rather than literature hunt we all associate academia with. Some very mundane finds, like e.g. mice or shrew bones, can be a surprisingly informative source of information, and Orkney, despite a rather small pool of species inhabiting it, provides a great environment for long-term studies on such finds. You will find more details on my research specifically in the second blog entry.

Further reading - author's work:

- Theses:

Romaniuk 2022 Rethinking Established Methodology In Micromammal Taphonomy: Archaeological Case Studies From Orkney, UK (4th millennium BC – 15th century AD). Dissertation submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Archaeology. Edinburgh, The University of Edinburgh School of History, Archaeology & Classics. http://dx.doi.org/10.7488/era/1960

Romaniuk 2015 From simple studies to complex issues: Research on rodent bone assemblages from Skara Brae, Orkney, Scotland. Dissertation submitted for MSc in Osteoarcheology course. Edinburgh, The University of Edinburgh School of History, Archaeology & Classics.

- Peer reviewed papers:

Romaniuk et al. 2020 Combined visual and biochemical analyses confirm depositor and diet for Neolithic coprolites from Skara Brae. Archaeol Anthropol Sci Vol. 12 is. 274 doi.org/10.1007/s12520-020-01225-9

Romaniuk et al. 2016 Rodents: food or pests in Neolithic Orkney. Royal Society Open Science 3(10): 160514. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.160514

BBC coverage of 2016 publication:

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-37690206

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-north-east-orkney-shetland-37699357

- Conference presentations:

Romaniuk et al. 2020 Statistics, taphonomy and representativeness: Making the most out of archaeological micromammal assemblages. In López-García, JM, Blain, H-A, Blanco-Lapaz, Ŕ & SE Rhodes eds. 3rd Meeting of the ICAZ Microvertebrate Working Group, September 1st – 2nd 2020, Tarragona (Spain): Abstracts Book. P. 10

Romaniuk et al. 2018 Micromammals, humans and environments – long- term perspectives on human-micromammal relationships on Orkney, Scotland: Preliminary interpretations. In Pişkin, E, Sevimli, E, Özger, G & G Durdu eds. 13th ICAZ international conference: abstracts. Ankara, Middle East Technical University. P. 174-175

Romaniuk 2017 “Of rodents and men” – The evolution and nature of human-micromammal relationships in prehistoric Orkney and Scotland. In Romaniuk, A, Steinke, K & R Guildford eds. Association for Environmental Archaeology Autumn Conference, Edinburgh 2017: Grand Challenge Agendas in Environmental Archaeology. P. 50

Romaniuk & Herman 2016 Rodent osteology from a zooarchaeological perspective – rodent skeletal remains from a Neolithic site at Skara Brae, Orkney, United Kingdom. In E Tkadlec ed. Rodens et Spatium July 25 – 29 Olomouc 2016, programme and abstract book. Olomouc, Palacký University Olomouc. P. 87

Further reading – other sources mentioned:

Berry 2000 Orkney Nature. London: Academic Press.

Haynes et al. 2003 Phylogeography of the common vole (Microtus arvalis) with particular emphasis on the colonisation of the Orkney archipelago. Mol. Ecol. 12: 951–956.

Martínková et al. 2013 Divergent evolutionary processes associated with colonization of offshore islands. Mol. Ecol. 22: 5205–5220.

To make a donation to any of the museums please follow the link and support us. Thank you.