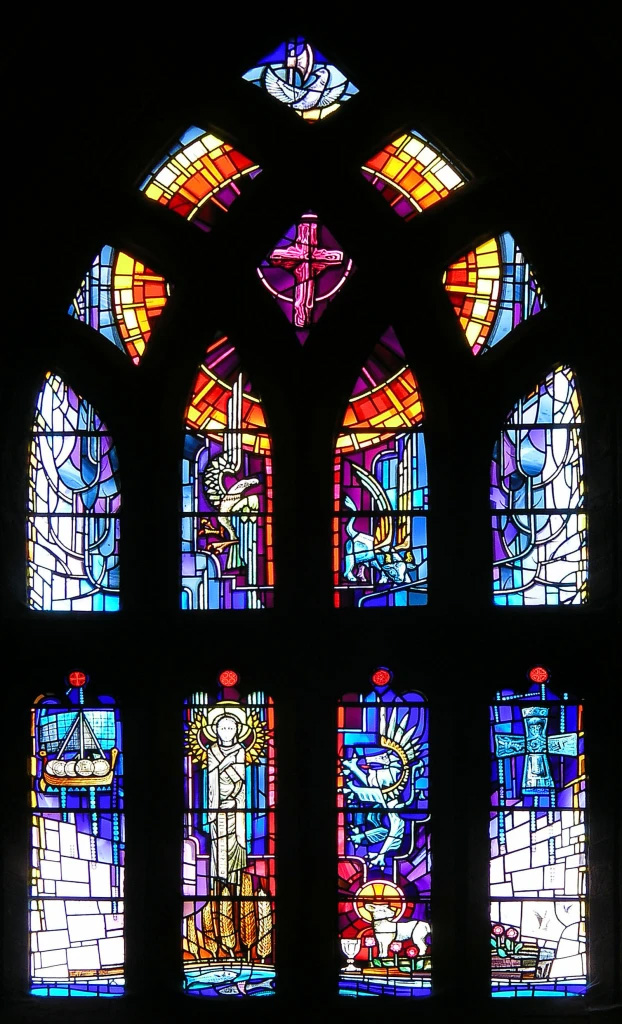

St Magnus Cathedral West Window

[Fran Hollinrake, St Magnus Cathedral]

If you have been inside or walked past St Magnus Cathedral any time since March 2021, it won’t have escaped your attention that there is significant work going on at the west end of the building. This is the first phase of a ten-year plan of remedial and conservation work, aimed at protecting our lovely cathedral for centuries to come.

The work currently being carried out is two-fold. Firstly, the previous wooden vestibule, installed in the 1920s, is being replaced with a new vestibule – there is an architect’s drawing of the finished article inside the cathedral at the moment. The second part of the work is the removal of 19th and 20th-century cement pointing, and its replacement with traditional lime mortar, which will help greatly with the problem of damp or wet stone. This phase of work should all be finished by the end of August.

For much of the past five months there has been a big scaffolding platform inside the west gable, which has enabled specialist glass conservators to clean the west window, inside and out, so it is looking really sparkly (I think that’s the correct technical term).

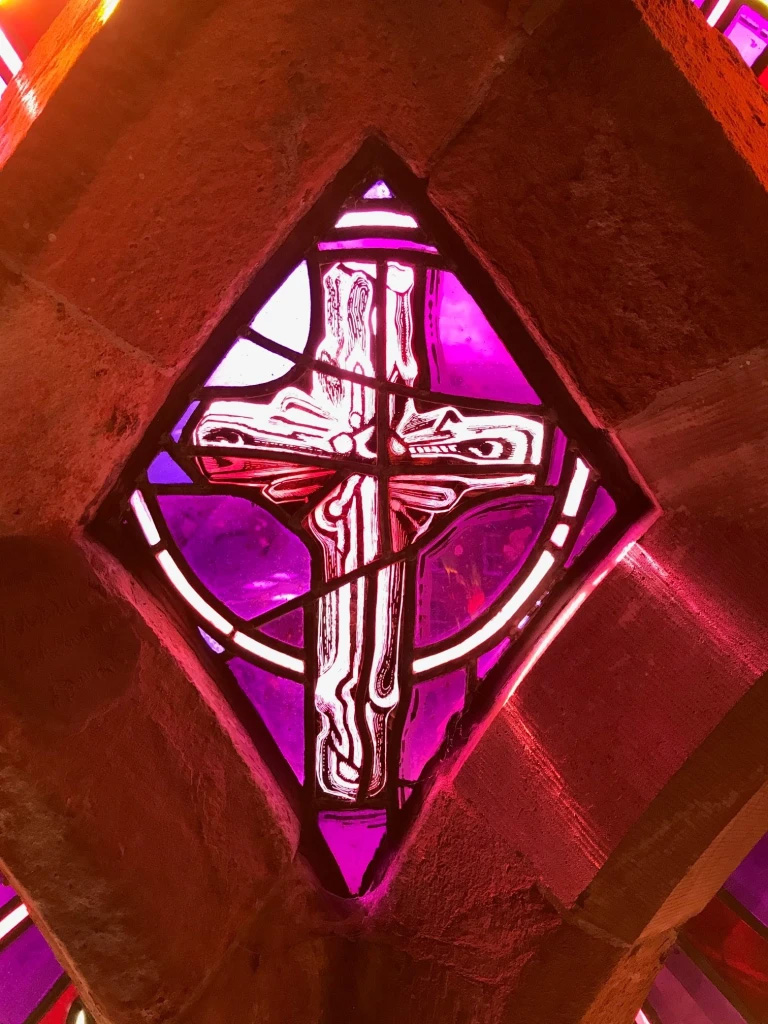

The scaffold platforms gave me the opportunity, hard-hatted and viz-vested, to climb the ladders under supervision, and examine the window close up – a rare privilege. I took some photos and shared them on social media, and they received many positive comments and questions, so I hope in this blogpost to answer some of those queries and reveal a few of the window’s secrets.

The west window was installed in 1987, to mark the 850th anniversary of the cathedral’s foundation in 1137. There were many events that year to celebrate this significant milestone, with gifts offered by the Norwegian royal family including a beautiful tapestry which hangs inside the south choir aisle. Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II came to Orkney to unveil the window officially, and the cathedral has a large leather-bound book, signed by Her Majesty, which names all the individuals, schools, companies, societies and organisations who contributed to the window’s cost.

Th artist chosen to create the window was Crear McCartney, an artist from Lanarkshire who had studied at Glasgow School of Art in the 1950s. On graduating, he was approached by Dom Ninian Sloane of the recently re-established Pluscarden Monastery (later Abbey) in the north-east of Scotland to work with himself and Br Gilbert Taylor at the monastery’s stained glass workshop. McCartney stayed with the monks for several years, and during the first year he lived as one of them; rising before dawn for the early offices, attending all the services, speaking to only a few people at set times, and taking all his meals in the monastic refectory. As meals were eaten in silence, one monk read continuously from the Bible. By the end of his time at the monastery, McCartney knew the Bible well and drew on its imagery, symbolism and stories for much of his subsequent career. The Pluscarden monks signed their names OSB (Order of St Benedict), while McCartney, in playful tribute, signed his OPIC (Only Presbyterian in Captivity).

In the 1980s, some of the early twentieth century windows in St Magnus Cathedral were in need of repair; the work was done by Pluscarden monks; their mark can be seen on several windows. Then in 1987 McCartney himself was approached to design the cathedral west window. For many hundreds of years the window tracery had been filled with plain glass, although following the First World War it had been proposed to have a stained glass memorial to Lord Kitchener, lost on HMS Hampshire off the west coast of Orkney in 1916. This scheme was abandoned in favour of the stone tower at Marwick Head, unveiled in 1926. Thus the west window comprised clear glass well within living memory (indeed some Kirkwallians are still unhappy about the window being stained glass at all).

Over his long career, McCartney is thought to have made nearly 120 stained glass windows for churches and other establishments – not just in Scotland, but in England, Europe and America. According to one source, he experienced synaesthesia, when senses become crossed over – he ‘heard’ sounds as colours and particular musical keys were translated into different colour schemes. Whatever music he was listening to as he designed the windows would be expressed in the colours of the glass. Another inspiration was the delicacy and colours of butterfly wings, a visual image which in his mind easily translated into stained glass design.

Luckily for us, we don’t have to guess too much about McCartney’s inspiration for the west window. For every window he created he hand wrote, in exquisite calligraphy, a full explanation. We are fortunate (thanks to my conscientious predecessor custodians) to have retained our original hand-written documents; according to his son, many places discarded or lost them. The main theme, we are told, is that of light, specifically the light of God. McCartney cites George Mackay Brown’s observation that ‘nowhere is the drama of light and darkness enacted with such starkness as in the north’.

The window, even from the ground floor, invites scrutiny of the details. The bottom right panel depicts a chunky Orcadian headland, in fact the cliffs at Yesnaby on Orkney’s west coast. Flying above the cliffs are two Arctic terns, birds often seen in an Orkney summer, flitting around the coasts. To the left of the headland is a lamb with a cruciform (cross-shaped) halo, representing the Agnus Dei (Lamb of God) – a symbol for Christ referenced in the Gospel of St John. Around the lamb can be seen five deep pink flowers which botanists will recognise as the Primula Scotica, a rare primrose only found in Orkney and the far north of Scotland. There are five of them to indicate the five wounds of Christ. The artist explains in his exposition that these images were inspired by Edwin Muir’s poem ‘Transfiguration’, where he writes of ‘flower and flock entwined as in a morning field’.

Next to the lamb are ears of healthy grain, and below them fish swim happily. There is clear symbolism here of the Biblical tale when Christ fed the five thousand with just a few loaves and fishes. Fish appear many times in the Bible, from the calling of the Disciples (‘I shall make you fishers of men’) to the use of the fish as an early secret symbol of Christianity. But these images are also firmly rooted in Orkney, showing the islanders’ lives of fishing and farming.

The bottom left panel depicts a Viking longship, in reference to Orkney’s Norse past and its place in the great Icelandic sagas. More specifically it is said to represent Rognvald Kolsson, nephew of St Magnus, builder of the cathedral, and later saint in his own right. The Orkneyinga Saga tells us that following the foundation of the cathedral (most likely around 1150, when it was consecrated), Rognvald took fifteen ships from Orkney filled with friends and supporters, plus the Bishop himself, and set off on a three-year round trip to Jerusalem. Along the way he charmed a French princess and burnt down a Spanish castle; when he reached the Holy Land we read that as well as paying homage at the religious sites, he also enjoyed some healthy sporting competition with his friends by swimming across the River Jordan. On his return to Orkney, the sails from his ships were taken and stored in the cathedral to dry.

The four central panels of the window show strong Christian images in the form of four creatures that traditionally represent the four evangelists and gospel writers, Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. Clockwise from bottom left they show an angel (St Matthew), an eagle (St John), a winged bull (St Luke) and a winged lion (St Mark). There are several explanations as to why this pictorial scheme, or tetramorph, has the saints depicted as living creatures, usually to do with the start of the Gospel, or the main theme, or how Christ is depicted in that particularly Gospel.

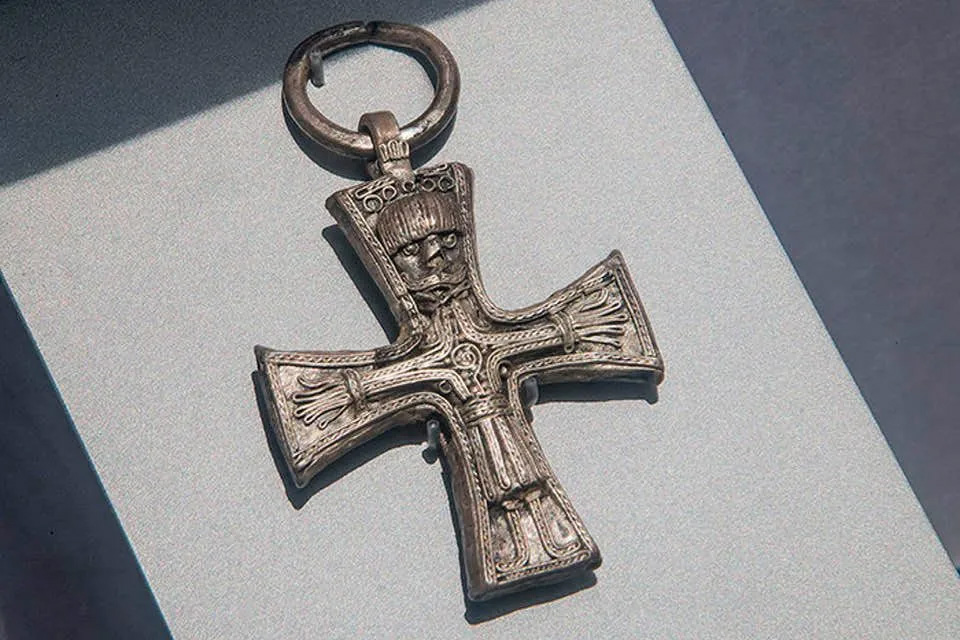

To the right of the tetramorph is a beautiful blue cross, inspired by a silver cross found in Trondheim in Norway, thought to date to the 10th century. Now on display at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) Museum, this small artefact is a reminder that Norway gradually became Christian in the 10th century, and that when St Magnus Cathedral was built, Orkney was part of the Norwegian kingdom. Shortly after consecration, the cathedral became part of the archdiocese of Nidaros, with its magnificent new cathedral in Trondheim.

The blue cross is answered higher up the window. In the centre of the sun-like circle is a pink patterned cross, the design of which is thought to date back to when the cathedral was a site of pilgrimage. We sometimes forget that St Magnus Cathedral was not built as a parish church (St Olaf’s in what is now St Olaf’s Wynd served that purpose); instead it was built to house the shrine of a saint – later two saints. In its Medieval days, everything in the cathedral would have revolved around the high altar, the constant rounds of services, and the shrine of St Magnus. Pilgrims came from all over northern Europe to venerate the remains of Magnus and to ask for his help. Like all pilgrimage towns, Kirkwall would have been full of lodging houses, eating places, guides, and souvenir sellers. Pilgrims would have been keen to purchase a special badge from their visit, to prove that they had reached the shrine and also as a memento of the journey. Many pilgrims’ badges were made of tin or lead, cheaply made and affordable to most (although there were no doubt more expensive versions to be had), and it’s very likely that St Magnus had his own pilgrim’s badge. In the 19th century a brass mould, or matrix was discovered in a niche in the cathedral – it is thought to date to Medieval times. The mould would have been filled with lead to make little crosses for pilgrims to buy; we aren’t completely sure that this was the design of the pilgrim’s badge but it would certainly have been used to create objects for devotional use. Crear McCartney used the cross’s design as the centrepiece for his beautiful window to show this essential aspect of the cathedral’s history. The original mould is now on display in the Orkney Museum.

Surrounding the cross is one of my favourite design elements in the window. Another stained glass artist, Christian Shaw, who worked with McCartney on many of his windows (and who has also worked on windows in St Magnus) said that McCartney had the ability to combine the very old and the very new into his designs; the great circle in the west window is a good example. The circle has been used in many religions and cultures as a symbol of the divine; it is a perfect shape, and has no beginning, middle or end. Here, it represents God. But the panes of coloured glass that make up the circle are not random – they are carefully shaped and spaced out to show the shape of Maeshowe Chambered tomb, and also the Ring of Brodgar stone circle, both prehistoric monuments. The glorious colours – red, orange, gold, yellow, not only depict the sun, but also the flare on the Flotta oil terminal, once a recognisable feature in Orkney’s night sky, as the chimney burnt off excess methane gas and made a ball of flame in the darkness. Old and new sites of power and technology, combined in one stunning image.

Finally, at the apex of the arch is the crowning image of the whole window. In quite a small panel (requiring the viewer to step back to look at it) at the top is a triangular window showing two design elements. The first is a white bird – a dove. In traditional Christian imagery, the dove can be a symbol of peace; when Noah’s ark sent out birds to see if land had been found, it was the dove who returned with an olive branch (also a symbol of peace) in its mouth, showing that God’s punishment was over and the flood waters were abating. The white dove is also a representation of the Holy Spirit, and in religious art (particularly that of the Renaissance) the dove is usually depicted at the very top centre of the image, radiating spiritual love downwards.

But behind the dove lurks something more sinister, something that brings us right back to Magnus again. For here is an axe, which the saga tells us was used by the cook Lifolf to kill Earl Magnus Erlandsson, on the orders of his cousin Hakon. This is a symbol of Magnus’s death, some would say martyrdom, and it hangs above everything else as a reminder that it was this act of violence that led to Magnus becoming a saint, and this cathedral being built.

Because this window is at the west of the cathedral, above the main entrance, it is best seen in the afternoon or evening, as it picks up the light from the setting sun and throws intense multi-coloured splashes onto the arches and columns of the nave. The effects change according to the weather, the time of day, or the month of the year. At midsummer the cathedral plays host to the St Magnus International Festival, which puts on a variety of musical events over several days. On one glorious evening I watched from the west end lighting desk as the window colours crept down the north side of the nave, swung slowly round to the east, and shone fully gold onto the communion table and organ screen, where the shrine of St Magnus would have stood during the cathedral’s Medieval heyday as a site of pilgrimage. It was a magical moment. Another serendipitous occasion came when as part of the Festival, religious paintings by Norwegian artist Håkon Gullvåg were hung between the pillars of the nave. The light shining through the window produced some amazing effects as it fell onto the paintings. The depiction of Noah’s Ark, suspended in deep space, was bathed in a rainbow of colour from Crear McCartney’s window – very fitting as the rainbow is the Christian symbol of God’s covenant – a promise to people on earth that the suffering was over and that He would love them always.

When you first walk into St Magnus Cathedral and see the west window, the first impression is one of vibrant colour and dynamic shapes. But look a little closer, and the details begin to reveal themselves in all their beauty. Once the conservation work is finished at the west end, the window will look truly magnificent.

All photographs by Fran Hollinrake, unless otherwise stated.

To make a donation to St Magnus Cathedral, or any of the museums, please follow visit MyOrkney and support us.

Thank you.