World War I – Battle of Jutland

The Battle of Jutland - 31st May to 1st June 1916

The Battle of Jutland in 1916 was the greatest naval engagement of the First World War and was the only time that the two Fleets would face each other in battle. Britain lost more ships and men than Germany, but retained control of the North Sea. Although both fleets did go to sea again, the lessons learned at Jutland made them more cautious.

The Kaiser refused to risk losing his navy, so the German High Seas Fleet was forbidden to face the British Grand Fleet in a decisive battle. Instead they limited themselves to shelling coastal towns in Northern England, in an attempt to draw out sections of the Royal Navy towards waiting German battleships and U-boats, where they could be picked off piecemeal.

The British had obtained a captured copy of the German code-book, enabling them to decipher German signals, so Admiral Sir John Jellicoe knew well in advance that the German High Seas Fleet was planning a sortie into the North Sea at the end of May 1916.

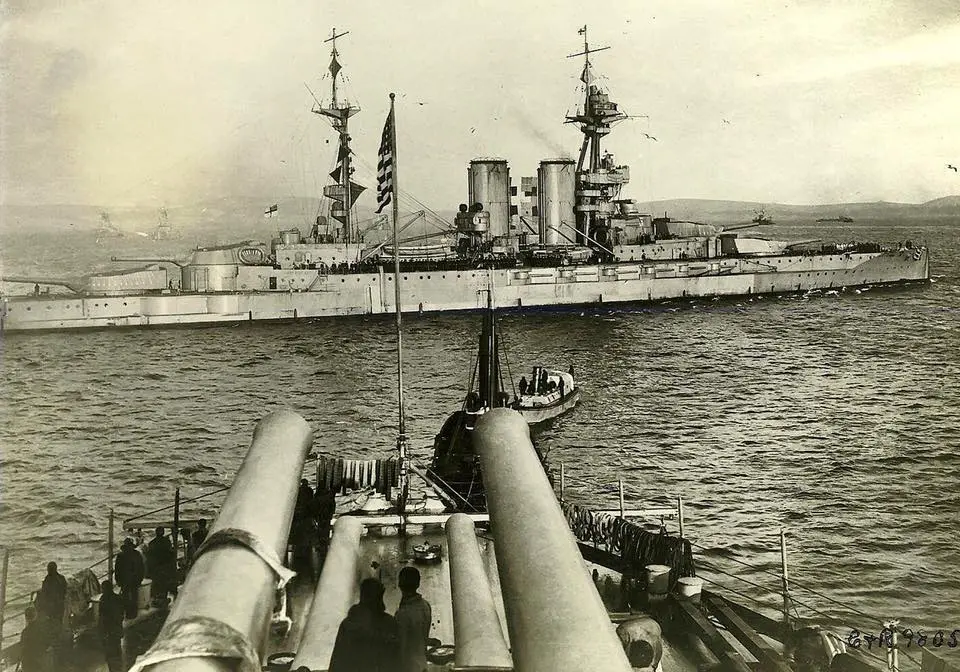

As Admiral Scheer ordered the High Seas Fleet to sail into the North Sea and carry out a sweep down the coast of Denmark, the Grand Fleet, led by Jellicoe in HMS Iron Duke, was already steaming from Scapa Flow.

“There seems to be something wrong with our bloody ships today.” (Admiral Beatty)

The problem lay with the way the ships were being handled. Beatty put more faith in rate of fire than in gunnery training, so cordite charges were piled up inside the gun turrets. The flash-proof doors, which should have prevented flames and high temperature gasses from an explosion being channelled down into the magazine where the cordite explosives were stored, were wedged open.

Meanwhile, Admiral Hipper’s battlecruisers were sent forward as bait, to try to lure Admiral Beatty’s battlecruiser squadron from the Firth of Forth towards the might of the waiting German Navy. The two sides met when scouting vessels from both Fleets went to investigate a neutral Danish ship. Hipper and Beatty’s battlecruisers opened fire on each other at 15:45 on 31st May. These were the first salvos of what became known as the Battle of Jutland.

Beatty’s force was augmented by four new Queen Elizabeth Class battleships, which caused considerable damage to the German battlecruisers. However, the Germans had superior firing accuracy, better range finders and more powerful armour-piercing shells. Beatty lost two battlecruisers, HMS Indefatigable and HMS Queen Mary, which sank when their magazines exploded. When Beatty found himself facing the High Seas Fleet he ordered his ships to sail north, leading the Germans towards the full force of the Grand Fleet.

Beatty was able to outrun his pursuers and join forces with Jellicoe. When Scheer encountered the Grand Fleet at 18:30 he faced the full broadside from the British ships. Beatty swung his battlecruisers into action again, with the loss of HMS Invincible, blown in two when its magazines also exploded.

Scheer gave the order to turn around and head for safety at 18:35. Jellicoe was not prepared to follow the High Seas Fleet in case of submarine attack and the danger of mines. The two fleets met again at 19:10, but Scheer ordered Hipper’s battlecruisers and destroyers to attack while Scheer made good his escape.

Small detachments of ships continued to exchange fire throughout the night of 31st May – 1st June, the last action coming at 02:30. Jellicoe ordered his ships back to Scapa Flow when it became clear that the High Seas Fleet had escaped back to their bases on the Baltic.

Jock Mears from Kirkwall served at Jutland on board HMS Tiger. His memories of the battle were recorded by BBC Radio Orkney in 1980s.

“Just about 3 o’clock the alarm bells rang and action-stations was sounded on the bugle, and we all closed up at our action stations. Now I was on the spotting top as they call it, right on the top of the mast. I had to make reports that they’d spotted smoke, and then they spotted masts.

About half past three, quarter to four, the order was given to open fire on the Germans. And actually the Germans opened fire about the same time, and it was all hell let loose. All you could hear was the scream of the shells going over you or dropping short of you, great splashes in the water. Then we were hit, and it was just like striking a great big bell.

Afterwards I found out that some of the 6th battery gun crew had been killed, and one or two fellows down about the coal bunker that had been killed and all. Of course we didn’t find out about this until after the battle.”

“The first battlecruiser squadron which had the Lion, Queen Mary, Princess Royal and the Tiger. The Queen Mary, she was sunk. She was in our squadron. Well, I actually saw her in the water, just the hull of her, and the men all scrambling about her decks. She was just about going under then at that time. I don’t think that there’d be very many of them picked up.”

In the morning of course the sea was all strewn with wreckage, all kinds of things floating about. Carley rafts and broken boats and wood and an awful lot of dead bodies. A lot of them had had life jackets on too, but they died, you see, of exposure. The Invincible, I saw her in a cloud of smoke, but I never saw her again. She was sunk and all, another battlecruiser.”

“The German Fleet has assaulted its jailor, but it is still in jail.”

As the German High Seas Fleet reached port first the Kaiser was quick to contact the news agency Reuters and claim a victory for Germany, saying: “The spell of Trafalgar is broken.” The Admiralty was slow in releasing any details, much to the frustration of the British public who had expected another decisive ‘Trafalgar’ style victory.

The losses on the British side had been greater, 14 ships and 6,097 men to Germany’s 11 ships and 2,551 men. Germany may have had fewer losses, but the High Seas Fleet had suffered terrible damage, and needed major repairs that would take a long time to carry out. The Grand Fleet returned to Scapa Flow on 1st June, refuelled and reported ready for action the following day. Jellicoe had retained control of the North Sea, but only just.

“The only man who could lose the war in an afternoon” (Churchill’s description of Admiral Jellicoe)

Admiral Jellicoe was heavily criticised for not pursuing and destroying the German High Seas Fleet, but he carried a heavy responsibility. Jellicoe knew the risks from torpedo attacks by destroyers and the hidden dangers of U-boats and mines and was cautious not to run into a trap.

If the British Navy, under his command, lost control of the North Sea then the German Navy could cut off the supply lines from Britain to her armies fighting in France. Germany would also be able to bombard the British coast, and potentially bring about the surrender of Britain and its Empire.

Jellicoe was later promoted to First Sea Lord of the Admiralty and command of the Grand Fleet that he had helped to create was passed to Admiral Beatty.

From the diary of Margaret Tait, Kirkwall. June 3rd

Rumours were afloat that a naval battle engagement was going on on Wednesday 31st May, but I could not believe it true. Last night Jim and I worked until 11pm putting new glass in a large picture for one of our Fleet men on the ‘Bellerophon’ when Maggie came in and told us a battle had really taken place and 10 of our ships sunk.

After that I could do no more work for thinking of all our men who had pictures in to be framed. I kept hoping all night that the news might prove untrue, so this morning one of the men off the ‘Royal Oak’, one of the ships in action came in with some pictures to be framed and told me it was all true. They can’t tell very much, so he said “It’s all very sad and that’s all I can tell you.”

We had heard that the ‘Marlborough’ was sunk but he said that she had come back all right in a little while. Poor chap, he was so hurt because he could not get word to his friends of his safety. All day on Saturday, the territorials were burying the dead in Longhope, so we were told.

What a gloom was cast over the town and how depressed we all were to think of our noble ships and brave sailors and officers going down that summer night on the North Sea off the coast of Jutland.”

Admiral Scheer took a reduced High Seas Fleet to sea once more on the 19th August 1916, less than three months after the Battle of Jutland.

His plan was to bombard Sunderland to draw out part of the Grand Fleet, which would be seen by the supporting Zeppelins and attacked by a screen of U-boats ahead of the fleet. This was to prove to Britain that the German Navy was by no ways beaten and still posed a real threat. Once again, the Royal Navy had intercepted the radio message ordering the German Fleet to sea and had sailed before Scheer had left port. Jellicoe was away on rest leave at the time, but joined the fleet when it was at sea. A British light cruiser, HMS Nottingham was torpedoed by the German submarine U-52 and later sank.

Jellicoe didn’t know if this was the result of a U-boat or a mine and fearing a trap he turned north to avoid a possible minefield. This detour prevented the two fleets from meeting. The German battleship SMS Westfalen was torpedoed by the British submarine E-23 and was towed back to port, while the Grand Fleet lost another light cruiser, HMS Falmouth, which was torpedoed by U-66.

One of Scheer’s Zeppelins, L-13, spotted the Harwich Force of destroyers and light cruisers sailing from the south and wrongly reported that there were battleships amongst their numbers. By the time the observer realised his mistake the Zeppelin had lost radio contact with the German Fleet and Scheer had abandoned his plans and headed back to port.

Jellicoe complained that the Grand Fleet needed more destroyers to protect it from the threat of U-boat attack. Scheer planned another raid by the High Seas Fleet, but the lesson learned from the 19th August was that he needed Zeppelins and U-boats.

Unfortunately for Scheer, unrestricted U-boat warfare was declared, which focused on sinking merchant vessels bringing food and arms into Britain, so he lost his escorting submarines.

This policy would ultimately lead to the USA entering the war on the side of the Allies.

The High Seas Fleet sailed once more around midnight on the 18th-19th October 1916, news of which was already known by the Grand Fleet in Scapa Flow. Fearing another attack by waiting U-boats and with insufficient destroyers to challenge them, Jellicoe decided not to put to sea. Scheer too was feeling the strain.

The light cruiser SMS München was torpedoed by the British submarine E-38, but was successfully towed back to port. Jellicoe was frustrated by the lack of success, saying: “They are very difficult to sink, or else our torpedoes don’t hit hard enough.”

By 14:00 Sheer ordered the Zeppelins to return home and turned the fleet around, claiming that the night would be too light to launch a torpedo attack. It seems that the rough seas, which meant that the destroyers couldn’t keep up with the larger ships, the torpedoing of the München and the fact that he was aware that the Grand Fleet knew that they were at sea may be the real reason why he turned back.

The High Seas Fleet would sail once more, on the 22nd April 1918, as far as the south-west coast of Norway before heading back to port. After that the crews of the ships mutinied and refused to go to sea again.

Scapa Flow Museum is currently closed for a major refurbishment project, funded by Orkney Islands Council, National Lottery Heritage Fund, Historic Environment Scotland, Highlands and Islands Enterprise, Museums Galleries Scotland, Scottish Natural Heritage and the Orkney LEADER fund. The project includes carrying out essential repairs to Pumphouse No. 1 and building an extension to house a new gallery, visitor facilities and café.

Visitors can virtually explore the buildings and former exhibitions at www.hoydrone.com/museum, a 3600 photo record of the main site museum site.

The Island of Hoy Development Trust website www.hoyorkney.com has a large Wartime Heritage section focusing on the WW2 history of Hoy.