Orkney Dialect

Author [Dr Tom Rendall, Orkney Museum]

The inspiration for my studies of the Orkney dialect was generated by a lifelong interest in the way dialect was used in Orkney and the variations that provide such a mosaic of nuances, words phrases and idioms. The way of life in Orkney has changed over the past century as a result of movement of people through migration and emigration along with the development of better transport links. Demographic changes as a result of the decision of islanders to leave their homes have encouraged the development of new networks of people from outside Orkney.

The inspiration for my studies of the Orkney dialect was generated by a lifelong interest in the way dialect was used in Orkney and the variations that provide such a mosaic of nuances, words phrases and idioms.

The way of life in Orkney has changed over the past century as a result of movement of people through migration and emigration along with the development of better transport links. Demographic changes as a result of the decision of islanders to leave their homes have encouraged the development of new networks of people from outside Orkney.

Although it is important to internalise and rationalise personal feelings and emotions, it is equally instructive to consider externalities and the ways in which those might impinge on the continuity of an island community.

The islands of Orkney are perhaps vulnerable yet relatively stable; able to maintain a form of equilibrium; sustainable yet subject to unknown or potential threats from external economic and social forces. Dialect is an emotive subject and is part of the culture and heritage of Orkney. The English language evolves with the passage of time so variations in the way people use local vernacular will not remain stable.

The inevitability of change cannot be ignored but the impact of the transformation, and the ways in which those changes are perceived by the people of Orkney, is central to the acceptance of transition and development of society in the county.

Some islanders might think that dialect is in danger of extinction and that there is little impetus or motivation to save it as a way of communication. The reason for the demise is often directed at the impact of the migration to the islands by people from other regions of the United Kingdom. The media influence is perceived as another contributory factor to the destruction of the Orkney tongue.

In this first part of the blog I will look at the origins of the dialect and look at how it developed into the Orcadian tongue used today.

Origins of the dialect and how it has developed

We need to cast our minds back 2000 years when Orkney was part of the Pictish kingdom .One of the enduring debates or discussions between historians and archaeologists and is on the subject of the fate of the Picts. Orkney was part of the Pictish kingdom from 300 – 800 AD. The size of the indigenous population of Orkney about 800 AD is not known but it would have been made up of Picts and Irish monks. Remains of churches and chapel sites are still be found in Orkney. When the people of Scandinavian lands arrived in Orkney, therefore, they would have found this mix of holy people and individuals who held allegiance to another kingdom.

The Picts may have spoken at least two languages: P- Celtic and Q- Celtic. P- Celtic was the language spoken in Strathclyde and Wales with Q – Celtic related to early Old Irish. There would have been some Irish Gaelic as monks inhabited some of the islands such as Papa Westray and Papa Stronsay.

There is no general agreement on what actually happened when the Scandinavians arrived in Orkney and there is no documentary evidence of the way in which they transformed the way of life. It has been mentioned by Hugh Marwick and others that there were Scandinavian settlers in Orkney long before the mass migration in the early 9th Century (Marwick 1929, 1992). As their ability to develop bigger boats increased so did their ambitions and their need to explore other lands. It is unlikely that the Picts and Irish monks were totally surprised by their appearance around 800 AD. It is possible that some of the population may have moved back to the north of Scotland leaving their land to the invading Norse people.

The arrival of the Vikings in the 9th Century heralded the appearance of a new language. Based on West Norse, the Orkney Norn developed and was the predominant language of the islands for about 700 years.

From the 15th Century onwards, however, the influence of Scottish English increased and, since the middle of the 18th Century it has been the language of Orkney.

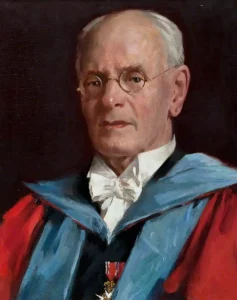

Dr Hugh Marwick

Dr Hugh Marwick (1929) undertook his research on the Orkney Norn and this provides the corpus of knowledge of the Norn along with Barnes (1998). Since the original publication of The Orkney Norn, a number of Scotland-wide surveys of lexical use have come to completion’ Since the 1920s, however, The Scottish National Dictionary (Grant and Murison 1929-76) has been completed.

This work provided a greater depth in our understanding of the use of Scots lexis. In combination with work associated with the Linguistic Survey of Scotland (Mather and Speitel 1985) it is useful in giving an overall picture of the linguistic situation in Scotland. Large-scale patterns sometimes obscure smaller-scale patterns; this is may cause some anomalies in regions such as Orkney which have relatively small populations but, historically, considerable variation in word and meaning from place to place.

As Millar (2007a) has said; “For the scholar of Orkney dialect in particular, there is little use in seeing that a word is found in Orkney; he or she would like to know in which islands or parishes a word is found.”

For centuries the Orkney Islands spoke with a Norse/Scots dialect, which replaced the Norn, which itself derived from West Norse. Although the exact date of Norse settlement in Orkney is not known it was likely that it extended over generations and possibly was complete by 900AD.

The settlers would have borrowed some words from native languages used in Orkney possibly based on Celtic sources but…. “The Norsemen were masters; they had no incentive to learn the native tongue…” (Marwick 1929 :xvi). According to Marwick the “Scotticizing” of Orkney would have been rapid from the middle of the 15th Century with the pledging of Orkney to Scotland in 1468.

It is difficult to know what the Norn was like before it was superseded by the language spoken in Orkney today but Marwick acknowledges the impact of the Scandinavian language and the way contemporary islanders use it albeit unwittingly:

“The speech of Orkney today must be termed Scots, but it is still richly stocked with words which were part and parcel of the Orkney Norn” (Marwick 1929: xxvii).

Orcadians could be said to have become increasingly bi-dialectal, speaking an Orcadian influenced Scottish Standard English together with Orcadian dialect of varying broadness and strength in a diglossic speech situation. The dialect spoken in Orkney is, therefore, part of Insular Scots language with many words base on the Orkney Norn and other lexical items used throughout Scotland.

Hugh Marwick has been an important starting point for scholars who are interested in the background to the dialect used in Orkney.

The work of two lesser known but equally important writers – Walter Traill Dennison and John Firth must be mentioned here They published their work prior to the appearance of Marwick’s The Orkney Norn in 1929.

Walter Traill Dennison

Walter Traill Dennison (1825–1894) was a farmer and folklorist. He was a native of Sanday where he collected local folk tales. He published these, many in the local Orcadian dialect, in 1880 under the title The Orcadian Sketch-Book.

Until his death in 1894, Walter Traill Dennison collected and recorded a valuable store of traditional local folklore, much of it concerning the sea and its mythical creatures such as mermaids. Through Dennison’s work, many Orcadian poems and stories exist today that might otherwise have been lost. He is responsible for bringing the dialect to the knowledge of the people and was one of the earliest writers in the vernacular.

Although the writing appeared as folk tales it was, nevertheless, a significant contribution to the collection of dialect words used in Orkney during the 19th century. In The Orcadian Sketch Book Dennison included a glossary of dialect words which supplemented the tales and poems in his book. This provided the reader with a guide to the meaning of the words but also highlights the use of dialect in the 19th century.

Dennison wrote “The author’s principal object has been to preserve the

dialect of his native islands from that oblivion to which all unwritten dialects are doomed and at the same time to present a part of our great human nature as it really existed, unsophisticated by the rules of polite society unelevated by education and unpolished by art.” (1880:vii)

John Firth

ohn Firth (1838 – 1922) was a joiner/wheelwright who lived in the parish of Firth. He was interested in all aspects of Orcadian life and wrote notes and journals of his observations. His book Reminiscences of an Orkney Parish was finally published in 1920 only two years before his death. This book also included a glossary of Orkney words as Firth was keen to promote the value of the local vernacular. He wrote: “The old Orkney dialect, with its quaint and peculiar diction, destined to no immediate or early extinction and wherever Orcadians meet in all parts of the world, its rich and beautiful accent and melodious tones awakens the most tender sentiments and emotions, and recall the most hallowed associations and cherished memories.” (1974:146)

The work of Dennison and Firth constitutes a rare collection of stories and tales of the lives of the people of Orkney in past centuries. They both had vision and the foresight to collect the words and phrases of the people. They also had a passion for bringing the dialect of the islands to a wider world. Dennison was the first writer to produce work in the dialect while Firth was able to highlight the value and the identity of the Orkney tongue.

References:

Dennison, Walter Traill, (1880) The Orcadian Sketch Book, Kirkwall, William Peace and Sons.

Firth, John (1974) Reminiscences of an Orkney Parish, Stromness, The Orkney Natural History Society.

Marwick, H. (1929, 1992) The Orkney Norn Dunfermline and Oxford WIA Murray -originally published by Oxford University Press.