The Scuttling of the German Fleet: 2019 Summer Exhibition at the Orkney Museum. Panel 3, Part 3. The Scuttling

The Scuttling

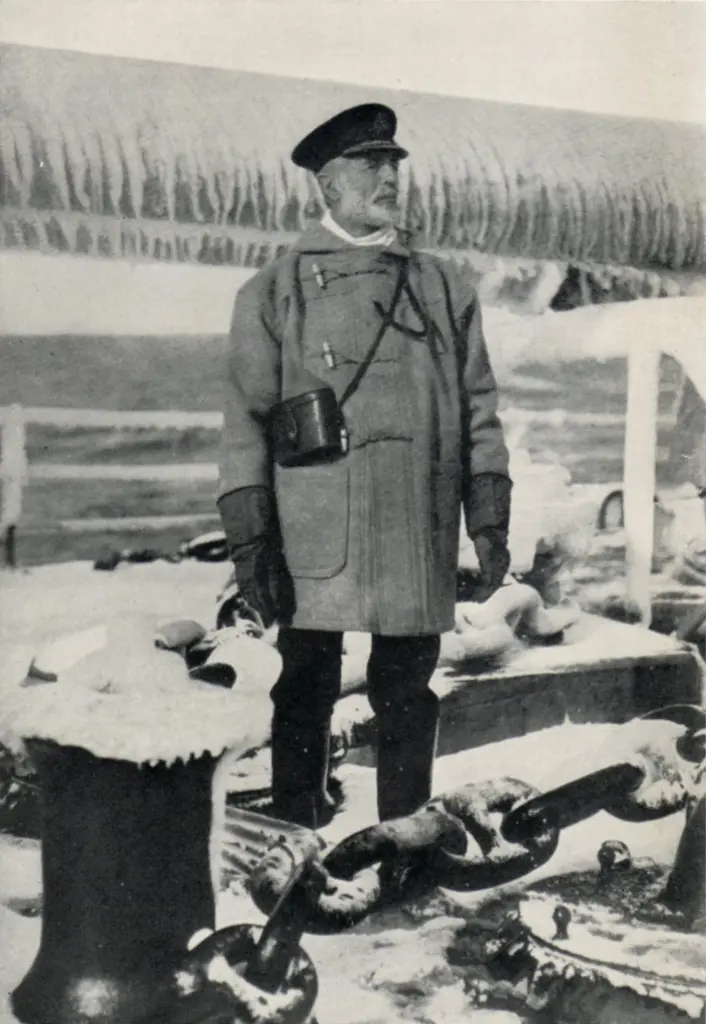

The 21st June was a lovely, sunny day. To Rear-Admiral von Reuter’s surprise, the guard ships of the 1st Battle Squadron sailed from Scapa Flow that morning to carry out anti-torpedo exercises with the Atlantic Fleet. The exercises had been postponed twice because of bad weather, and the commander-in-chief of the Atlantic Fleet, Admiral Sir Charles Madden, was keen that it should be carried out without further delay. To von Reuter, who was wearing his dress uniform and medals, it looked suspicious. He thought that the ships would return at speed and seize his ships. He decided that he could not postpone scuttling the ships any longer. He had the signal flags hoisted.

To all Commanding officers and the Leader of Torpedo Boats. Paragraph eleven. Confirm.

To which the reply was:

To the Commander of the Internment Force. Paragraph eleven is confirmed.

‘Paragraph Eleven’ was a 19th century student drinking term, which had a military tone, and meant ‘keep drinking’.

When exactly the order was given is unclear, but it was some time between 10.00am and 11.00am. The order took some time to reach all the ships, as some were anchored out of sight of von Reuter’s flagship, SMS Emden, and had to wait until it could see the signal flags of other ships. The torpedo boat destroyers were the last to get the order. The crews of most of the ships had no idea what was going on, as the officers were instructed to keep it secret. Some did tell their crews when they guessed that something was going on. The concern was that the British might find out if everyone knew, or that the Soldiers Council would inform on them. The first sign of the scuttling came when one of the naval trawlers noticed flags flying on some of the ships and their crews taking to small boats. On closer investigation, the light cruiser SMS Frankfurt was seen to be sinking, but it was later beached by the British. A message was sent to Fremantle’s 1st Battle Squadron. The ships headed back to Scapa Flow at speed.

Around midday, the tolling of a ship’s bell was heard coming from the former flagship, SMS Friedrich der Grosse. This was the signal to abandon ship. At 12.16pm it rolled over and sank. The first of the 52 ships to sink that day was on its way to the bottom of Scapa Flow. A group of around 200 school children from the Stromness School was enjoying a sightseeing trip on board the tug Flying Kestrel when the German ships began to sink. It was an exciting and frightening spectacle for the children from the older primary school classes and the secondary school. The children didn’t know it then, but they were watching history being made.

To make a donation to any of the museums please follow the link and support us. Thank you.